Causes Of Pain In People With Dementia

When it comes to the topic of dementia and pain, several causes may make a person with dementia feel pain.

Note that potential pain causesfor individuals with dementia are the same for everyone else.

Dementia on its own does not generally cause physical pain as this typically comes from other conditions.

One of them is the fact that persons with dementia are at higher risk of injuring themselves or falling.

Other factors that can make the suffering person feel pain include:

Sitting or lying on the same spot for hours without moving.

This increases the risk of joint stiffness, muscle contraction, constipation, or pressure sores which can cause discomfort and severe pain.

Also, there are other conditions as well:

- Leg ulcer dressings

What Is Pain And Why Assess It

Defining pain is complex however, it is generally agreed to be an unpleasant, emotive and personal experience . Pain is generally split into two categories: nociceptive and neuropathic . Nociceptive pain relates to the normal physiological response to pain where a traumatic stimulus causes the release of endogenous chemicals, such as prostaglandin and histamine . This leads to the transmission of an electrical impulse to the brain via the nervous system for perception and subsequent reaction . Comparatively neuropathic pain is the result of damage or dysfunction of the nervous system . This may occur in the central nervous system as a result of persistent stimulation of the nervous system, despite the removal of the causative agent, or in the peripheral nervous system where damaged interneurons may send spontaneous, unwarranted, signals to the brain .

| Inclusions | Exclusions |

|---|---|

| Meta-reviews, systematic reviews or reviews with the primary focus of pain assessment tools in older adults with dementia | Literature failing to provide unique analysis of original or pre-existing data |

| Literature no more than 10 years old | Literature which primarily focuses on pain management, with pain assessment as an adjunct subject |

| Literature published in English |

Clinical Implication For Practitioners

It is imperative that practitioners use a consistent approach to prevent, detect, and manage physical discomfort, and to recognize that pain may worsen behavioral disturbances. This differentiation is critically important to allow selection of the most appropriate pharmacotherapeutic regimens, specifically an analgesic regimen in lieu of an antipsychotic agent. Because of frequent tracers and penalties against nursing facilities with regard to antipsychotic use, it may be prudent for facilities to assess pain and possibly treat with an analgesic trial before administering antipsychotics for agitation and aggressive-type behaviors.

Herr and colleagues suggest a consistent process for the assessment and management of pain in patients unable to self-report pain, including infants/preverbal toddlers, and critically ill/unconscious, dementia, intellectual disability, and end-of-life patients. Specific considerations for dementia and end-of-life populations are as follows:

In summary, patients with advanced dementia approaching the end of life have a high symptom burden. Pain is often underreported in this patient population because of their cognitive impairment. However, health care providers must anticipate this challenge and screen for and treat potential pain when possible.

You May Like: What Age Do You Get Alzheimer’s

Detecting Pain In Persons With Dementia

As dementia progresses, it can affect a persons language skills to the extent that they are not able to express when they are in pain.

Some affected persons may not even remember how they hurt themselves or the source of their pain which adds to the challenges of trying to communicate about their pain.

Caregivers should, therefore, know how to detect when a person is suffering from dementia and pain so that it can be treated as soon as possible.

Because persons with dementia will experience pain differently, at times it may be possible to ask directly whether a person is in pain.

This is where you shoot direct questions like does it hurt, are you in pain? Is it sore? and they will give you an answer.

However, when a person is not able to communicate how they are feeling, perhaps because they have advanced dementia, their behaviors might give you a clue when they are experiencing pain.

Some of the behaviors include social withdrawal or becoming increasingly agitated. Other non-verbal cues that a person may use to communicate that they are in pain or distress include:

Tools For Assessment Of Pain In Nonverbal Older Adults With Dementia: A State

- Keela HerrCorrespondenceAddress reprint requests to: Keela Herr, PhD, College of Nursing, 452 NB, The University of Iowa, 50 Newton Road, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA. ContactAffiliationsAdult & Gerontological Nursing , College of Nursing, The University of Iowa The University of Iowa , Iowa and The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston , School of Nursing, Texas, USA

- Karen BjoroAffiliationsAdult & Gerontological Nursing , College of Nursing, The University of Iowa The University of Iowa , Iowa and The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston , School of Nursing, Texas, USA

- Sheila DeckerAffiliationsAdult & Gerontological Nursing , College of Nursing, The University of Iowa The University of Iowa , Iowa and The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston , School of Nursing, Texas, USA

Read Also: Does Cognitive Impairment Lead To Dementia

Criteria For Considering Reviews For Inclusion

Definitions of criteria for inclusion of reviews in the meta-review followed an adapted SPICE structure . We included systematic reviews of pain assessment tools involving adults with dementia or with cognitive impairment. Dementia and cognitive impairment were defined according to the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Heading vocabulary. Dementia was defined as an acquired organic mental disorder with loss of intellectual abilities of sufficient severity to interfere with social or occupational functioning . The Dementia MeSH term covers more specific subheadings such as Alzheimer Disease or Vascular Dementia. Cognition Disorder was defined as: Disturbances in the mental process related to thinking, reasoning, and judgment . We did not include Learning Disorders, defined as: Conditions characterized by a significant discrepancy between an individuals perceived level of intellect and their ability to acquire new language and other cognitive skills. . Examples of learning disorders of this type are dyslexia, dyscalculia, and dysgraphia.

Table 1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Barriers To Recognising Pain

Training for healthcare staff in recognising pain and providing adequate pain relief to patients in long-term care facilities can be limited.6,7 Pain, although highly prevalent in nursing homes, is often not documented in nursing notes 7 staff are reliant on patients self-reporting their pain.8 This is problematic for patients with dementia who may struggle to verbalise their symptoms. Lack of time to observe patients, particularly in hospital settings, can be a significant issue.8 Inadequate staff continuity can lead to isolated snapshots of what the patient is experiencing,8 rather than the full picture. Establishing a pattern of the patients pain is essential if analgesia is to be appropriately evaluated. More accurate pain assessment may come from engaging with family members or carers who know the patient well.3

Pain can be misinterpreted as behavioural disturbance. A positive association between pain and aggression or agitation has been demonstrated in several studies.3,6,7,9,10 Consequently, misidentification of pain can lead to psychotropic drugs being inappropriately prescribed.11 If pain is not successfully treated, behavioural symptoms may mask the underlying issue and exacerbate distress.

Read Also: Activities For Early Stage Dementia

Overall Completeness And Applicability Of Evidence

We analysed 23 reviews for data extraction and included data from eight of these. Whilst we could have been more strict in our interpretation of the criteria for a systematic review and exclude a greater number of potentially eligible records before reaching the stage of data extraction, this would not have necessarily restricted the analysis to reviews with higher AMSTAR scores. It would have given us a smaller number of records for data extraction, and while this would have saved us time in the data extraction process, we do not believe that it would have changed the final outcome and the findings. It would also have reduced the number and range of tools assessed.

We analysed 28 tools included in eight reviews. However other tools are also available and were included in some of the reviews we excluded because they did not provide psychometric data for extraction. The review by Stolee et al. , for example, covers 30 tools, including The Proxy Pain Questionnaire, The Pain Behavior Measure, the 21-Box Scale, and the Pain Thermometer, among others.

Furthermore, this meta-review does not cover a new tool recently developed in France by the Doloplus Collective team ALGO Plus . To our knowledge, the tool has not been included yet into a systematic review.

Last Few Days Of Life

NICE recommends that a palliative care approach is advisable for patients with dementia.14 The GSF prognostic indicator guidance can help generalists identify when palliative care should be involved.21 When patients are no longer able to swallow, as part of the natural dying process, it is important that their pain control is still optimised and subcutaneous medication may be needed with the use of a syringe driver. The specialist palliative care team can help ensure that symptoms continue to be controlled.

Also Check: What Test Is Given For Dementia

Assessment Of Methodological Quality Of Included Reviews

The PRISMA guidance on systematic reviews explains how, in carrying out a systematic review, it is important to distinguish between quality and risk of bias and to focus on evaluating and reporting the latter . The authors encourage the reviewers to think ahead carefully about what risks of bias may have a bearing on the results of their systematic reviews . In our meta-review, the risk of bias may reside in each review considered for inclusion, as well as in the original studies that comprise that review. We did not access the studies to be able to accurately judge their quality or risk of bias. In terms of each review, we assessed risk of bias in terms of how the review was conducted and the criteria applied for inclusion/exclusion. Critical appraisal was carried out by two independent reviewers, using the AMSTAR systematic review critical appraisal tool . Critical appraisal and evaluation of potential bias was carried out at the time of data extraction, after screening was completed on the basis of the inclusion criteria.

Settings Where The Tools Were Studied

The tools were studied in a variety of settings and with varied patient populations. The terminology used to describe settings varied, and those which appeared to be in non-acute settings included: long-term-care, nursing homes, dementia care units, psychogeriatric units, rehabilitation facilities, aged care facilities, residential care facilities, long-term care facilities, palliative care but also, geriatric clinics, care homes, residential and skilled care facilities, long-term-care dementia special care units, and a residential dementia care ward .

The terminology to refer to hospital settings also varied, with reference either to patients and/or type of services: e.g. hospital patients in a long-term stay department, psychiatric hospital setting, hospital medical care unit, dementia special care units in hospital, hospital patients and older hospital patients.

Also Check: When Alzheimer’s Patients Get Angry

Dementia & Alzheimer’s Disease

There are very many questions people have about dementia one of the most popular ones revolves around dementia and pain.

Some people wonder whether its true that persons with the illness experience pain or they just fake it.

Honestly, persons with dementia will feel pain and it is usually challenging to assess.

Lets look at some of the areas that both persons with dementia and carers should be knowledgeable about when it comes to pain and dementia.

Managing Pain For Individuals With Dementia

When you suspect that a person is going through dementia and pain, it is advisable to seek medical attention.

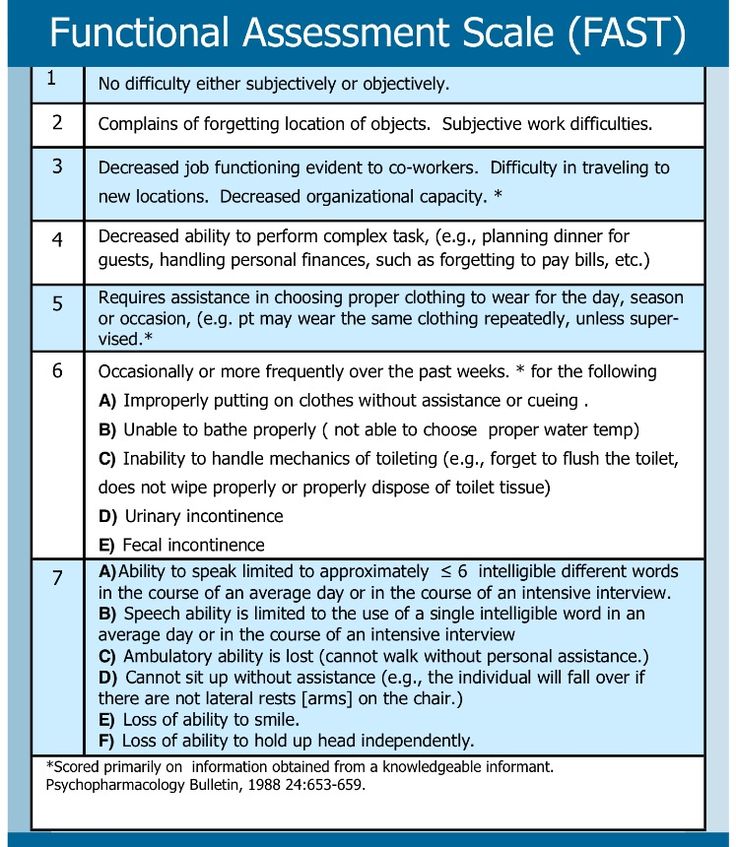

Doctors have special tools that they can use to detect pain in seniors who have dementia.

The health care workers are also in the best position to prescribe appropriate pain medication depending on the cause of pain.

Some of the drugs that doctors may prescribe include opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, laxatives, and analgesics.

There are also non-drug therapies that can help with dementia and pain.

Depending on doctors instructions they can be implemented alone or in combination with pain alleviating drugs.

Examples of therapies that can help include:

- Pet, music, or aromatherapy

If a person needs to be on long-term pain management, you can always consult different professionals like tissue viability nurses, a general practitioner, physiotherapist, or a pain specialist team in your locality to get expert advice on effective pain management strategies.

Don’t Miss: Can A Ct Scan Show Alzheimers

Pain Assessment In Advanced Dementia

Twelve studies assessed the PAINAD . Overall, the level of evidence for the PAINAD tool was limited . Whilst there was an adequate level of evidence for construct validity , very good level of evidence for internal consistency , and reliability , there was inadequate evidence for cross-cultural validity and responsiveness . There was doubtful level of evidence for structural validity .

Pain In Dementia: Use Of Observational Pain Assessment Tools By People Who Are Not Health Professionals

Correspondence to:

Funding sources: This work was supported, in part, through a grant from the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation.

Conflict of interest: Thomas Hadjistavropoulos acknowledges that he is one of the developers of the PACSLAC-II which is one of the scales discussed in this article. Nonetheless, he has no commercial interest in the PACSLAC-II. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Pain Medicine

Also Check: Will I Get Alzheimer’s

What Can Be Used To Manage Pain

Research into pain medication for older patients with dementia is currently limited.6,12 The European Association of Palliative Care advises that pain should be managed holistically 13 there should be an emphasis on both pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment.13,14 However, pharmacological interventions are more commonly used 15 non-pharmacological measures such as re-positioning or physiotherapy are typically overlooked.15 Reflexology, reiki and music should also be considered 3 however, further research is needed.3

With regard to pain management in patients with dementia, the clinical challenge is often in balancing benefit over the risk of treatment. With increasing age, patients are more likely to have comorbidities such as renal disease this can influence which opioid is prescribed and limit the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories. Transdermal patches may be useful in patients with cognitive impairment increasing medication compliance and reducing tablet burden. There is also increasing interest in the use of topical preparations lidocaine and capsaicin for neuropathic pain, which may be of benefit to this group of patients.16

Although there are no guidelines specifically for pain relief for patients with dementia, recommendations are outlined in Table 2 based on guidance from the British Geriatrics Society, NICE and the World Health Organisation.17,18,19

Search Methods For Identification Of Reviews

The following databases were searched : Medline, All EBM Reviews , Embase, PsycINFO, and CINHAL the searches were carried out all on the same date . Additional searches included the Joanna Briggs Institute Library and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database. Further data was retrieved through reference chaining. No grey literature was sought.

Table 2 Literature search: databases and details of numbers of records retrieved

The search strategy used a combination of text words and established indexing terms such as Medical Subject Headings . The search was structured by the relevant SPICE concepts. Search terms were identified by comparing published search strategies adopted by reviews in similar areas , or on the subject of pain or pain management tools, not specifically for the same patient population , using the search strategy for retrieving reviews outlined by Montori et al. . Detailed search strategies were optimised for each electronic database searched .

Table 3 Search strategy

You May Like: Mediterranean Diet And Alzheimer’s

Ability To Identify Gradations In Pain

We had hypothesized that participants would be able to differentiate among gradations in the pain experience. Means and SDs of PACSLAC-II and PAINAD scores for gradations of pain intensity are presented in . The ability of LTC nursing staff and laypeople to differentiate among gradations of pain was tested using a 2 x 4 mixed-methods MANOVA with repeated measures, using the PACSLAC-II and the PAINAD as dependent measures. The MANOVA yielded significant results. There was a significant between-groups multivariate effect using the Wilks criterion =7.36, P< 0.05, partial 2=0.10). There was also a significant within-subjects multivariate effect =392.20, P< 0.05, partial 2=0.95). Finally, there was a significant interaction effect =4.76, P< 0.05, partial 2=0.19).

Concurrent Validity

As expected, a positive correlation was found between the majority of scores on the PACSLAC-II and the PAINAD, confirming the concurrent validity of the two tools separately for each observer group. That is, PACSLAC-II and PAINAD scores on six out of seven of the pain videos were significantly and positively correlated for laypeople . All of the PACSLAC-II and PAINAD scores were significantly and positively correlated with each other for LTC staff . includes a full list of correlation coefficients, separate for each observer group.

Data Extraction And Management

Data were extracted by two reviewers independently using a set of data extraction forms which was developed for the meta-review: 1) the AMSTAR checklist , 2) two forms for data about the reviews and 3) one form for data about the tools . The latter included a field for data extraction on the user-centredness of the tools, informed by Dixon and Longs work on the development of health status instruments . The data extraction forms were both paper-based and built into a MS Access database. At the time of data extraction, the reviews eligible for inclusion were screened further on the basis of availability of psychometric data of tools. At this point, we found that some of the reviews initially identified as being eligible for inclusion in the meta-review did not provide psychometric data of tools and were subsequently excluded . Data about the characteristics of the tool were extracted from the reviews we did not search for, nor retrieve, the original tools. The reviews were synthesised using a narrative synthesis approach.

Also Check: Do Dementia Patients Get Headaches